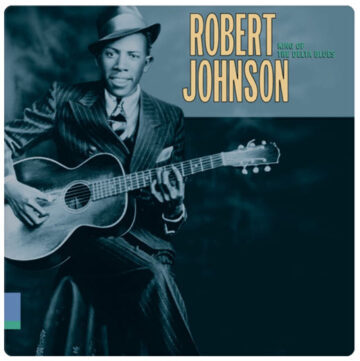

A brief recap of Robert Johnson‘s history and legacy is in order before delving into the music itself because many find it hard to disentangle the story from the music, the man from the myth. Anyway, it’s a wicked story.

Johnson was uneducated. His father ran out on the family, while his mother remarried before she took off as well. As a 19-year-old, Johnson married a 16-year-old who tragically died during childbirth while Johnson was on his “ramblings,” or travel, and upon his arrival home was shunned by the community. So he left town and began associating with blues legends Son House and Willie Brown, who thought Johnson at that time was an appalling guitarist.

Now for the legend.

Johnson moved to yet another part of town, remarried, and six months later reappeared in Mississippi as the best guitar player House and Brown had ever heard. Apparently, he had gone down to the crossroads to sell his soul to the devil who tuned his guitar so he could play it any way he wanted. He fuelled his own myth by singing about the devil and the crossroads.

He was such a good guitar player people began repeating the myth and perhaps even subscribing to it a touch. Intrigued by it were especially a young Clapton, a would-be bluesman named Mick Jagger, and maybe even an old Clapton who not only recorded “Crossroads” in the 60s with the supergroup Cream but issued a full album of Johnson covers in 2004, entitled Me and Mr. Johnson.

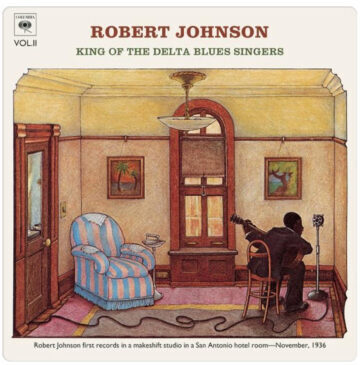

Anyway, after Johnson’s alleged encounter with Satan he became a full-on blues man, travelling with a group of blues musicians whose names sound like SNL parodies: Memphis Slim, Shakey Horton, and Howlin’ Wolf. Fortunately, in 1936 Johnson happened to record 29 songs in a hotel room in Texas, 42 songs including alternate takes (which really are fundamentally different than the originals). These are Johnson’s only recordings. On August 16th 1938, Johnson was slipped a poison bottle of whiskey and died soon after, but not before allegedly crawling on all fours and barking like a dog. It’s thought a jealous husband or spiteful relative did him in. You just can’t make this stuff up.

When Johnson sings about the devil, it’s haunting, but when he sings about hot tamales, it’s funny. His myth prevents people from understanding that he was just a great storyteller, adept at embodying the spirit and characters in his songs. Of course people are attracted to the sexy, mysterious mythology, but it’s misleading: the guy had extremely long spiderlike fingers, a perfect ear for music, and he practiced a lot – he did not make any deal with the devil.

Different tunings allowed him to make various bass patterns accessible – they weren’t just used with a capo to play the same shapes in a different key. He wasn’t the first to use open tunings, but he did more with them, and definitely pioneered his own tunings.

“Crossroad Blues” demonstrates Johnson’s graceful, but subtle command of the instrument. That wailing slide in the intro has got to be the most classic intro in blues. Throughout the song, the open tuning slide riffs are prominent, but the details are in the interspersed bass notes, which anchor the song. They add density and fullness. He relishes the tone of his slide by being just behind the beat, milking each slide for full value. Fretting while wearing a slide is tough; you have one less finger and the slide gets in the way of the others, but he still manages to syncopate, and seamlessly switch between fingers and slide. His technical ability was unmatched, but it sounds effortless because he sings simultaneously with such passion and rhythm. The way his voice and his guitar intertwine with call and answer is like a duet.

But songs like “Phonograph Blues (Alternate Take)” demonstrate his mastery of standard tuning, slide-less blues. This song is tuned down a half tone with a capo on the second fret. Bass notes ring out and bounce around. The melody lingers, bends and trills. The chords move along the neck in octaves, and the phrasing switches from a shuffle, to abrupt pauses, to sustain. But this is a crude assessment: the playing is saturated with little responsive habits unique to Johnson. Self-taught musicians have their own esoteric ways of playing, and perfectly replicating Johnson’s music is hard. Indeed, a reliable transcription of Johnson’s music with the proper tunings wasn’t in print until 1999. Despite juggling all these guitar duties, he sounds playful when he sings, as though it’s easy.

Technical explanations for such emotional music are only useful for guitar players and those who need to remember Johnson was a mortal human being, flesh and blood. “Soulful” music takes on a new meaning in his case. He had his soul still. The devil’s been taking too much credit for too long. But maybe looking at Johnson’s music through the mythological perspective gets us closer to the depth of feeling he inspires. For all the immense technical playing, the music is raw and that’s the point. This music is intended to be felt, not analyzed. If you hear this music at night, alone, it evokes that sublime feeling of introspection and solemnity you get at graveyards. For this reason, not for the myth and not for the technical prowess, no real fan of music can ignore Robert Johnson.