So soulful and revelatory was Jimi’s playing that his catalogue inspires players and composers across every genre.

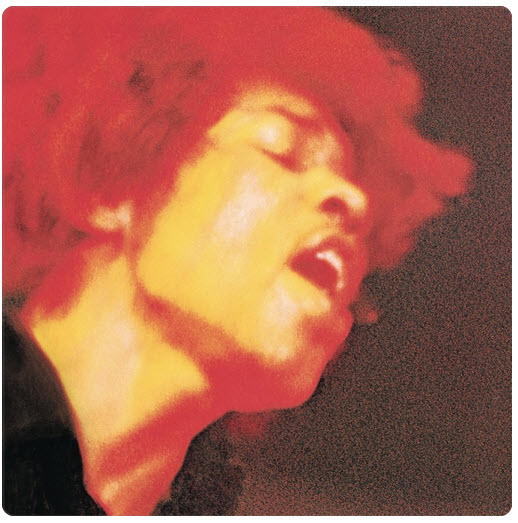

It was on May 3, 1968 that Jimi Hendrix and his crew spent an entire day playing one song, “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” over and over again in the studio: it was an abbreviated version of a much longer blues-rock invention called “Voodoo Chile” that Jimi had improvised with Steve Winwood on the organ for the the double album Electric Ladyland. The album itself took its title from the groupies who offered themselves up nonstop to Jimi. The Slight Return version turned out to be one of the most widely played covers of any Hendrix composition, most notably by Stevie Ray Vaughn, but no one has ever come close to the creator’s own performance on the sonic masterpiece that Jimi laid down in that 12 track studio in New York known as The Record Plant. Both long and short versions of the song are found on the album, but it’s highly significant that Jimi chose to close the album with the shorter version, the one that took the entire day of May 3 to record.

Jimi was a perfectionist, and an extremist, who would often demand multiple takes from Mitch Mitchell, drummer, and Noel Redding, bassist. It drove them to distraction, particularly since there was very little in the way of security at the studio. Dozens of friends, groupies and hangers-on would congregate in the studio, to the delight of Jimi and to the hostile consternation of the band. Hendrix was both a genius and a terrifically nice person, who gave out and received a great deal of love both with his music and his person. He didn’t hesitate to speak about the evolution of his music as a spiritual journey. He was also wholly aware of his talent, and he considered “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” as one of his most transformative compositions. Here’s what he had to say about it:

“Voodoo Child” is the new American anthem, the self-assurance song, not coming from us to you, but coming from the next world too. A song about a cat singin’ he’s gonna chop down a mountain with the sides of the hand, just building himself up, there’s nothing wrong with that at all. It’s a very straight rock type thing, very simple, very funky, our own little funk theme, dedicated to all the people who can actually feel and think for themselves, and feel free for themselves, and dedicated to our friends from West Africa.”

The track is near orgasmic in its intensity, and it’s also of Jimi’s strongest vocal performances. Keep in mind he never thought of himself as a singer at all, and called himself “more of an entertainer and performer than a singer”. This is an impassioned performance from the opening note to the closing, and one of the best recordings by a blues-rock trio ever put down on tape. The only other supergroup that came close was Cream, and it’s worth noting that one of Jimi’s biggest fans was none other than Eric Clapton, who was a first-rate traditionalist on the fretboard, whereas Jimi was an exciting innovator.

The album also represents Jimi’s first attempts at editing and mixing, though this was done in collaboration with the great Eddie Kramer. The result: a stoner’s sonic paradise, and an ear-opener of the first order, whether straight, sober or otherwise.

And yes, Stevie Ray does a somewhat credible job on his version of “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)”, though to this listener there is something rushed and superficial in SRV’s rather soulless playing. It’s an imitation that is both original and good, though (imho) that old dictum applies here: what is good about it isn’t original, and what is original about it isn’t good. Take a listen to the studio track (recorded live, btw) by Jimi below: if you haven’t heard it in a while, or perhaps never have heard it, you will be transported by the authority, inventiveness, and sheer energy behind Jimi’s playing. Technology has advanced considerably in the forty-five years since this track was laid down, but this recording was fifty years ahead of its time, and sounds as fresh and as vital, perhaps even more so, than anything being released today.

Jimi was a master of sustain and controlled feedback, as well as phasing; his special sound effects, both live and edited, were as carefully calculated as those of any classical or operatic composer, and from the beginning of his recording career he used such effects intentionally, programatically and judiciously (take a listen to “Third Stone From The Sun” from his debut album). There is no current electronica musician who has approached or surpassed Jimi’s composing abilities. Don’t let the genre of blues rock fool you into thinking that Hendrix was merely a gifted rocker who used psychedelia to record some weird shit: here’s what Jimi had to say about the direction his music taking:

“I’d like to get into more symphonic things, so kids can respect the old music, traditional, like classics. I ‘d like to mix that in with so-called rock today. I want to get into what you’d call ‘pieces’, behind each other to make movements.”

The result? – take a listen to “1983” from Electric Ladyland. It is a true classical composition in sonata-rondo form, with an Aaa B A C A B/A seven-part rondo with Bolero rhythms. Who knew? – Hendrix knew, Hendrix the stoned, freak-flag wearing, guitar-burning guy who played his axe with his teeth, or behind his back, or upside down, knew exactly what he was doing and why.

It’s worth noting that the black audiences Stateside who might have embraced his music treated him rather contemptuously. What he recorded made little sense to them, so far was it removed from Motown and their love of soul and blues music. It’s also worthy of recall that Hendrix was a sensation as soon as he arrived in England. England had a longstanding love affair with American blues, but in addition was also far more sophisticated than mainstream American audiences, and thus the UK music fans and critics alike were open to hearing innovation in sound, approach and technique. Hendrix was not the first or the last American musician , jazz, blues, rock or otherwise, to find serious recognition and acceptance in Europe before making it big in the U.S. And he won’t be the last.

“Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” and the album Electric Ladyland, belongs in every music lover’s library, and in every guitarist’s repertoire. No other artist has had as many recordings released after his death as Hendrix, simply because he made a point of putting every moment he ever spent in the studio down on tape. Much of it is brilliant; all of it is highly listenable, and hardly any of it is believably replicated by subsequent interpreters, regardless of their talent or technique or technology. So soulful and revelatory was Jimi’s playing that his catalogue is one of the very few in the blues/rock genre that will prove to inspire players and composers across every genre. Jimi Hendrix is the Johann Sebastian Bach of the guitar: a superb improviser, a relentless composer, and a prolific artist whose ultimate legacy will last for centuries. He is that important.