“I love you in a place where there‘s no space and time”

This is an immortal work in the annals of pop music, written by a Howard Hughes lookalike semi-recluse named Leon Russell. On the occasion of Willie Nelson‘s 70th birthday in 2003, Leon and Ray Charles performed the tune in concert in the presence of Willie and reduced him to tears. Check out the video on YouTube. If it’s many years it‘s been since you felt your own waterworks flow, this song is going to do it to you.

The composer breaks a few songwriting rules. Jimmy Webb advises, “Try to avoid ‘this is my song‘ territory. It‘s a little corny at this point in time to hear the writer advertising himself… especially since this genre has been so brilliantly exploited by the masters.” (Tunesmith by Jimmy Webb). Well, the masters he was referring to include the team of Elton John and Bernie Taupin, who penned “Your Song” (1970) as well as Jim Croce, who came up with “I‘ll Have To Say I Love You in a Song (1972). Russell claims his song was written a few months earlier than Elton‘s, and there‘s little doubt that Elton‘s piano stylings on his tune closely mirror that of Leon‘s. In any case, they‘re both great songs. Of the two, I prefer Leon‘s, lyrically and musically.

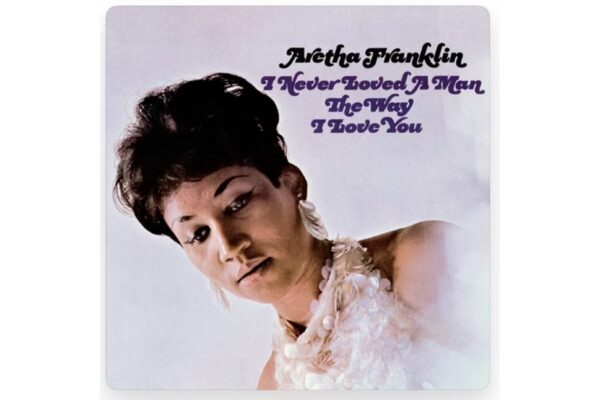

As for Aretha Franklin, if you haven‘t heard her version, I‘m sure you know a good deal of her catalogue. She is rightfully The Queen of Soul, and remains so to this day. Her early albums were consciously crafted examples of hit-making. Her first album from 1967 contains one of the most moving soul recordings ever made, I Never Loved A Man (The Way I Love You). Jerry Wexler, the Executive Vice President of Atlantic Records is known to have said he worked with only three musical geniuses in his lifetime: Ray Charles, Bob Dylan, and Aretha. For the liner notes of Aretha‘s first album, Wexler has this to say regarding this recording:

“Every time Aretha began a song, the musicians would shake their heads in wonder. After each take was completed, they would rush from the studio into the control room to hear the playback. Producers, engineers and musicians alike were entranced by Aretha‘s purity of tone, her tremendous feeling for inspired variation and her unparalleled dynamics.”

He then went further to say:

“The stimulation and the fire that lit up the musicians and the studio people had not burned so free and joyous at Atlantic since our great early years when we were recording Ray Charles.”

One key factor in Aretha’s vocals that remains seldom discussed: she was a superb pianist, classically trained, with an exquisite sense of dynamics. On many of her records, particularly her early ones, she accompanied herself on the piano while singing, a feat which is seldom attempted and which rarely succeeds. In Aretha’s case, her mastery of the piano led to the sheer beauty and creative artistry in her vocal work.

By 1973 Aretha had begun to explore the possibilities of jazz-flavored songs. Her first album in this arena was The Other Side of the Sky and it sold poorly. Then she reunited with Jerry Wexler, Arif Mardin and Tom Dowd that resulted in one of her finest albums ever. It was called Let Me In Your Life and featured the session work of such people Richard Tee, Bob James, Hugh McCracken, Eumir Deodato, Stanley Clarke, Rick Marotta, and Bernard Purdie.

The standout track on the album is “A Song For You” and was intended to be, since it is the closing track. In many ways the story of Aretha‘s life, the song is a personal plea for forgiveness from one‘s lover, made by the narrator/performer who has spent her life on the road and has “acted out my life in stages with ten thousand people watching”. Aretha plays the piano, while Richard Tee supplies the support of his elegant and heart-felt organ playing. In addition, Cornell Dupree on guitar, Willie Weeks on bass, Bernard Purdie on drums, and Ralph MacDonald on percussion complete the ensemble.

This is one of her most restrained and beautiful performances. She has the ability to sing what from anyone else would be a minor overlooked word in the lyric, such as “please” in the final verse and give it an interpretation and conviction that comes from the heart. The inventive jazzy ending gives the listener hope that her plea will be heard, and this ending is a significant departure from any other interpretation of the song.

That brings to mind what I‘ve written elsewhere about the insight Aretha brings to the work of the songwriter and the lyricist. When writing about Elvis versus Ricky Nelson attempting the same tune, I was prompted to compare the singing of Aretha with that of Dionne Warwick. In my view there is no one that truly compares with Aretha except Ray Charles, and it‘s no coincidence that they have both recorded “A Song For You” with the same result: a heart-stopping unforgettable masterpiece that yes, reduces grown men to tears.

The function of high art, of tragedy, in the view of the ancient Greeks, was a purging of the emotions, and a recognition of the nobility of life and human endeavor. With Aretha, popular music achieves the status of high art.