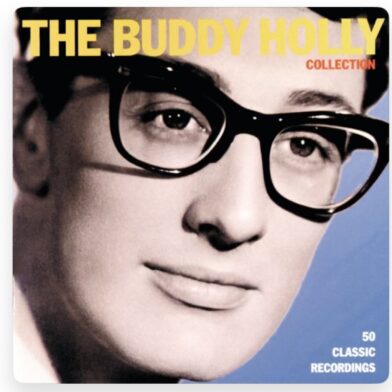

When the B side of a record becomes the A side: the story behind Buddy Holly’s “Well Alright”.

~ updated by popular request

Listen to the songs on the first three Beatles albums. Take their voices off, and it‘s Buddy Holly.” ~ John Mellencamp

Let‘s talk about B sides. They were often looked at as throwaways, since there was no percentage in putting out two great sides on a 45 rpm single. After all, a single was short-lived, perhaps 2-3 months at most, and then there would be a call for another hit. Many pop careers in the ’50s and ’60s lasted only a couple of years. Why not stretch it out and double the sales?

A few groups used the B side of a single to demonstrate other facets of their talents. If the A side was a vocal, they‘d show off their instrumental skills on the B side. And vice versa. Get 3 or 4 hits in a row and you could issue an album called “Greatest Hits of — or “Best of “etc.

Then you‘ve got Buddy Holly. He had a surefire hit when he recorded “Heartbeat”, a younglovetruelove number that was mainstream pop. For the flip side, he made one of the greatest recordings ever made by a pop/rock singer, one that deserves both study and acclaim. The song is called “Well Alright” and we recommend it highly as an essential track.

The tune features Buddy strumming his guitar, Jerry Allison on brushed cymbals and triangle, and Joe Mauldin on bass. It‘s a deceptively quiet number, with Buddy singing rather softly and straight ahead, without his usual hiccupped would-be Elvis manner. His performance on “Well Alright” is unadorned, unpretentious, and demonstrates both strength and tenderness.

It‘s common knowledge that the Beatles were devout fans of Holly, going so far as to derive the group’s name of The Beatles from Holly’s group The Crickets. This song in particular impressed Paul and John for its quiet but powerful dynamics, a quality The Beatles incorporated in many of their own songs.

Rolling Stone writer Dave Marsh claimed that “If Buddy Holly had lived to see the Seventies, he would have been heralded as the Father of the Singer/Songwriters.”

Truly great music has dynamic range: by that I mean there‘s a change that may move from a quiet sound to a loud sound, from a moderate sound to an immoderate sound, from diminuendo gradually (or suddenly) working its way to crescendo. It‘s this change that affects the listener emotionally.

The common criticism of rock music is that it‘s a one-dimensional event, appealing only to the lowest common denominator. After the first recordings of Elvis Presley there was no going back, but in the best pop/rock music, there is a sense of going forward. Buddy Holly exemplifies that growth that built upon the excitement of rock music with the strength of solid songwriting and an appreciation of how to build a song through dynamics.

Too bad it didn‘t last; by the late Seventies we were easing into the formulaic dance of Saturday Night Fever and the decadence of the early Eighties. Subtlety disappeared in favour of the completely obvious. Music since then has both lost its soul and its importance.

Most contemporary rock/pop music is recorded at one level; it has a sameness of sound texture and tonal colour – thus the importance of remembering how songs such as “Well Alright” could reinvigorate today’s music.

More than sixty-five years after his death, Buddy Holly‘s music has a legacy worth exploring. There is so much more in his work than meets the eye. Listen again to “Well Alright” and see if you don‘t conclude that in this case the B side is truly the A side.

Yes, a really wonderful song and you are quite right to flag it up. Apparently it was composed by Buddy after finishing a gig and flopping into a chair in the hotel while the others went out. By the morning the song was completely finished when the Crickets came down for breakfast: tune, chords, words … the lot.

It’s incredibly simple to play, as any guitarist will know, but the tune is pure divine inspiration – I say divine because I really don’t know how to explain the origin of inspiration (does anyone!); perhaps out of the ether may be another way of putting it, although somehow more prosaic.

Amazingly it didn’t do that well in the charts on both sides of the pond! Explain that!

For me, it’s Buddy’s best song, his second to last composition and a wonderful gift to us all.

Finally, someone else gets how great this song is. My favorite pre-Beatles pop rock songs are Runaway and Well…Alright. So different from the Blind Faith cover, which misses the intimacy and most of the dynamism. (But I still like it.)