Brian Eno’s 77 Million Paintings exhibition asks the big questions: – What Are We Talking About and What Is Art For?

Brian Eno stands at the leading edge of the music world as a pioneer of ambient music and electronica through his initial work with Roxy Music and Robert Fripp, followed by subsequent independent releases under his own name, notably Music For Airports in 1978. His compositions and productions have been a major influence on pop music since the early 1970s. Through his work with such ground-breaking acts such as Talking Heads, Daniel Lanois and U2, music has evolved in ways unimaginable before Eno forged a new world of ambient and steady-state wonders. He speaks of the recording studio as his “sonic paintbox”.

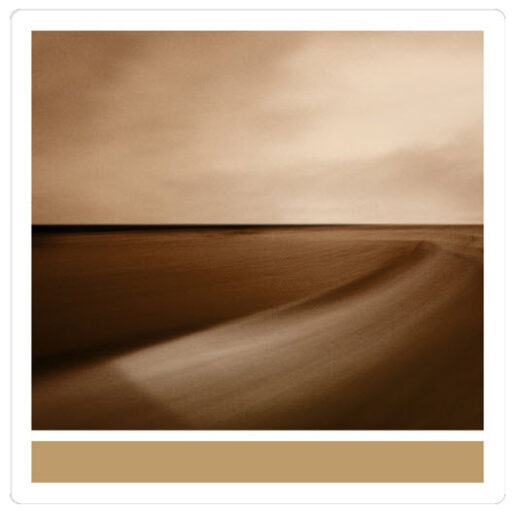

A traveling exhibition of his work in the visual arts is called 77 Million Paintings – though Eno confesses he has underestimated that number and that the images generated by the software are in the billions. In fact, in all the many years Eno has been working with the 550 or so paintings that form the four image banks, he has never seen the same image twice.

What is also becoming widely known among music fans is that Eno has been working for more than 30 years in the visual arts, and is now being feted worldwide in the art world for his work with light, sound, and painting. His exhibition consists of one installation, but that one installation generates millions of images. It’s a mind-blower consisting of nine screens, two piles of vermiculite, and a barely noticeable but intriguing ambient music soundtrack. The computer-generated images are mesmerizing.

June 2023 saw the release of the 77 Million Paintings soundscapes, with six songs of ambient complexity designed to accompany the exhibition.

Since the inception of 77 Million Paintings in 2006, the work has been exhibited in churches, halls, on the wings of the Sydney Opera House, and in countless galleries. People love this work: they are in fact spellbound by it, spending hours watching the changing of the images. As Eno stated recently: “This must be an experience that all of us are craving.”

Touring with the exhibition he often takes time out to lecture to interested audiences who may or may not be aware of the format of the evening. At the concert hall Brian Eno plays no music. He shows no paintings. What he does, in a short and brilliant two and a half-hours, is inspire his audience into new ways of thinking about music, about art, and about life.

He starts with a discussion of Copernicus and the earth-shattering publication in 1543 of “De revolutionibus orbium coelestium” (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), which demonstrated convincingly that the Earth was not the centre of the universe. Eno then takes his audience on a journey that led through Darwin’s “The Origin of Species”, through to cybernetics, and Eno’s own discovery of the work of Stafford Beer, a 20th century thinker and engineer. Beer stated: “We cannot control systems; we can only set up systems that can become self-controlling”.

Eno is so full of humour and self-deprecation that he always has the audience wanting more. Obligingly, he speaks of his interest in the pop music of Phil Spector, and how “Classical Music comes from the Divine, whereas Pop Music comes from the testicles”.

Eno also states his own credo, and how he came to it early when he saw his hard-working postman father falling asleep in his food at the end of the day. From that day on “the most important decision I ever made,” said Eno ” was the one not to have a job”. Brian Peter George St John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno (his full name) was all of nine years old. He decided at 11 to become an artist when his uncle gave him a book of Mondrian paintings. In art school Brian Eno fell in with other artists who were also musicians. He heard talks from composers such as John Cage and Morton Feldman. He suddenly understood that classical composers had lost the plot, and that these new composers were onto to something important. Further, that Phil Spector had done something special in creating his Wall Of Sound.

Terry Riley’s composition “In C”, and Steve Reich’s work “It’s Going To Rain” were major influences on Eno. He began experimenting with tape recorders and sound loops, with multiple recorders playing those loops simultaneously, but out of sync deliberately. The result became the basis of Eno’s music:

“Your ears cease to hear the common elements and then focus in on the uncommon. The brain of the listener becomes the composer”.

In the late 1970s he began to experiment with video recorders, light, and paintings with the same philosophy that he applied to music. For Eno, paintings and music are limitless. He uses technology, particularly synthesizers and computers, to generate new ways of creating and experiencing art: sound without lyric, story, beginning or end, and paintings that move, generate colours never seen before, and control light in a very precise way but with a slow rate of change.

The Big Questions for Eno remain: with music, with literature, with cinema, with painting – What Are We Talking About and What Is Art For? Eno makes a few suggestions without claiming that he has found the answers to these Big Questions:

1. Life is a continuum, an adventure and an information flow coming from all sides. Long gone are the days of the hierarchal pyramid ( which he humorously described as: first God, then the Englishman, then horses, then women, and then the French).

2. Art is everything we don’t have to do. Art is what happens when function ends. Painting, pop records, novels, etc. have no function.

3. What is play for children turns into art for adults.

4. The whole value of art is that you can enter into it with complete abandonment.

5. There is great value in surrender, whether that surrender be to sex, drugs, religion or art, four things in which all societies engage.

6. Last, but not least, civilization is an evening out, whether that be a music concert, a gourmet dinner, a political gathering, or a memorial service. Wherever human are gathered, endless possibilities arise. As he recently told The New York Times:

“That, more and more, is the feeling that I’m fascinated by: What happens to humans when they multiply their feelings together? We’ve been so atomized over the last 50, 100 years and told that we have to have our own completely independent lives and that the real human is the one who can stand alone. The real human, to me, seems like the one who can support his neighbors and work with them. That’s a feeling that I pursue. Whenever I see it, I want to encourage it.”

Such commentary only begins to suggest the depth of the civilized and eclectic passions of Brian Eno: from Copernicus to Dick and DeeDee’s recording of “The Mountain’s High”: from Darwin to Mondrian to John Cage to the generative complexities of computer software, as Eno contrasts the insignificance of our species with our grand imaginative powers.