At one point Bob Dylan called Tim Hardin “the greatest songwriter alive today.” This week marked the 40th anniversary of Tim’s death (December 29, 1980) from a drug overdose, and any reputation he has probably rests on the covers of his remarkable songs, notably Rod Stewart’s take on ‘Reason To Believe’, Colin Blunstone’s beautiful version of ‘Misty Roses’ featuring a beautiful cello interlude, as well the earlier famous cover of ‘If I Were A Carpenter’ by Bobby Darin in the mid Sixties.

Darin’s cover version was despised by Tim, who drove his car off the road and banged on the hood in frustration when he first heard the Top 40 arrangement Darin gave the song. Of course, the cover was a big hit and made Tim a considerable amount of money, money he badly needed to fuel his drug habit. Tim forgave Darin only slightly for debasing his song on the Hit Parade. The heroin and cocaine habits dominated the rest of Tim’s life, and his wife divorced him. In 1980 Tim died a sad and lonely death of a heroin and morphine overdose in Los Angeles. He was 39 years old and had squandered both his writing talent and his considerable performing abilities. He left behind a body of songwriting and recording that deserves to be known and appreciated in the current climate of musical insincerity that sticks resolutely to its one octave of computerized and digitized formulaic mediocrity.

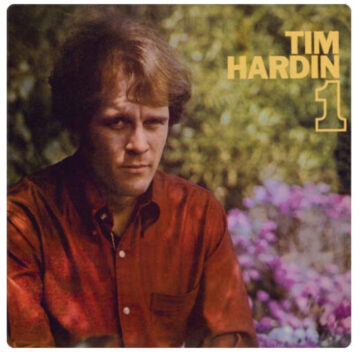

Verve Records issued a double LP some years ago in their Select Double series; they kept Tim’s first two releases wholly intact, along with the wonderful accompanying photographs and liner notes. If these two albums were all Tim ever accomplished, he would still deserve Dylan’s accolade. Fortunately, after several years of struggle and poorly produced releases, Tim released another masterpiece with a remarkable album in 1971, entitled Bird On A Wire. All three recordings are indispensable. Tim Hardin is one of the most under-appreciated figures in 20th century music. He was as talented as Hank Williams, as troubled as Chet Baker, and as ill-suited to ordinary life as Lenny Breau, Jim Morrison or Janis Joplin. When he was focused on his artistic work, there was no one better at what he did. No one.

Tim was a soulful singer, owing as much to jazz as to blues, and owing as much to Hank Williams, Ray Charles and Mose Allison as he did to the New York folk scene. His music was piano-based for one thing, whereas most of the singer-songwriters of the time preferred the guitar. Piano led him places that distinguished him from almost all other writers and performers of the time. In his own words:

“I’ve always thought of myself as a jazz singer. Jazz to me is just personal. Everyone who is a jazz player, according to my definition, plays like only he plays. No else plays that way. I also feel that jazz is blues is jazz is blues is. . . Blues is not a restrictive term… If it ain’t true it ain’t jazz and if it’s true it’s the blues.”

Tim Hardin was brought up in Oregon where his parents were classical musicians. After a stint in the Marines, he ended up in New York in the early 1960s with plans to become an actor. Soon he was hanging around Greenwich Village with people like Fred Neil, John Sebastian, and Bob Dylan. With his first album for Verve in 1966 Tim came to immediate prominence, but his best work was done by the time he was thirty. The words he wrote for the closing number of his second Verve album in 1967 came to be all too true all too quickly. The song was called ‘Tribute to Hank Williams’ and contained the lines “I didn’t know you but I’ve been the places you’ve been.” It’s almost as if Tim knew his own self-destructive tendencies would lead to an untimely death in imitation of Williams.

In the mid to late Sixties, Hardin was much beloved by a wide variety of musical connoisseurs, though he was far too unreliable in his personal life to have much of a career. Nonetheless, the simplicity and beauty of his songs, as well as the depth of romance and despair in his voice, were celebrated by jazz, folk, and blues devotees. He set the stage for the confessional singer-songwriter style of such performers as James Taylor, Ron Sexsmith, Bon Iver and countless others. It’s worth noting that Rod Stewart recognized Tim’s genius, covered his songs on many occasions, and secretly supported Tim financially to the end of his days.

Tim attracted great musicians in the studio to work with him: such luminaries as John Sebastian, Gary Burton, Ralph Towner, Ralph McDonald and Joe Zawinul flesh out the three recordings I’ve named above. The first two Verve recordings reveal folk and blues influences, while the Columbia release of Bird On A Wire is jazz-inflected and experimental. The musical setting of the Columbia album is exquisite, a model of restraint and soulful creativity that shows off the power of Tim’s expressive vocals. He has travelled considerably beyond the verse, verse, chorus format of his early work, and this may not appeal as much upon first listening, but give it a chance and it will grow on you. I’ve been listening to this album since it came out – it’s an album to which you have to pay attention. It’s definitely not something to put on while you’re doing something else.

Disturbingly, the photo of Tim on the back cover of this album shows the toll his lifestyle had extracted: Tim was not even 30 in 1971 when the album was released but he looked ten to fifteen years older. The album seems to be a chronicle of his marriage, his divorce, and his longing to reconcile with his wife Susan and their young son Damion. It’s hard to believe this is the same youthful man who seemed so vibrant, alive, and exciting just five years before. And Tim knew it – in the words he wrote in his song ‘Andre Johray’ for the Bird On The Wire album – “a poor man with money don’t stay quite the same.” Somehow the producer, arranger, and guitarist Ed Freeman managed to harness Tim’s talents over several sessions.

In addition to being a great songwriter, Hardin was a brilliant cover artist: check out his version of Fred Neil’s ‘Blues On the Ceiling’, as well as his take on Leonard Cohen’s ‘Bird On The Wire’. His recording of ‘Georgia On My Mind’ may well make you forget every other reading of this song. For a self-fulfilling prophecy of the most tragic dimensions, I suggest you listen to Tim’s cover of the old standard ‘A Satisfied Mind’.

Tim came to grief and desolation due to his dependence on drugs: he was a restless and aggressive personality who couldn’t construct any semblance of an ordinary life. In spite of this he left us with a legacy of unparalleled tenderness, sensuality, and non-formulaic musicianship in his quest for artistic expression. It’s not too late to become a Tim Hardin fan; once you do, you will call on this restless soul again and again in search of your own satisfied mind. Dylan was right: for some years Tim Hardin was the greatest songwriter alive. And just as no one sang Dylan like Dylan, no one sings Hardin like Hardin.

I saw Tim at the Royal Albert Hall in the mid ’60s. Here he was also heckled by some people, I don’t know why.I remember being mildly disappointed as the songs he sung sounded disjointed compared to his records of which I had his whole collection. I count myself as fortunate I was able to see him before his sad demise.

Well-written article on Tim Hardin!

Sad and tragic such a gifted man went awry due to his addiction.

A beautiful soul. When I listen to him sing, “If I Were A Carpenter”, “Reason to Believe” and “Lady from Baltimore” it feels as tho he’s still alive, even tho it’s been 40 years. His music comes from the heart.

I’m wondering if it was Tim Hardin or Tim Buckley who played a solo gig in San Francisco in a big empty auditorium in the early-to-mid 1980s. There were a few fold-down seats in the middle of the otherwise empty room, and he sat in one facing us, the audience, maybe 30 people tops. There were two hecklers in the back who came in late and kept saying weird things and clearly made him uncomfortable. A few people told them to shut up and the interruptions made him so uncomfortable that it pissed off everyone. He ended the show early thanks to them. I still wish I’d had the nerve to stand up and tell them to shut up, but a couple of guys did, to no avail. I’ve been trying for years to remember if it was Tim Hardin or Tim Buckley. I loved both. If anyone has a clue, please respond. TY.

It couldn’t have been Tim Buckley, because Buckley passed away in 1975. Tim Hardin performed at the Boarding House nightclub in 1973. The Boarding House was not as large as the auditorium you described, but Hardin didn’t pass away until late 1980, so the above information may offer the clue(s) you requested.

I needed to read this to know Tim Hardin, I was always playing his music even though it would make me feel bad sad in a good way.

Like now I’m listening to his music and I’m not sure if I should as I’m really in a bad place. I need to escape the darkness that is causing me pain and fear. I actually believe that I died in a motorcycle accident five years ago last month, and to make matters worse I have just found out that Tim died 1980 (year my eldest son was born).

I know I know that it sounds unbelievable but there is a reason.

From 1968–1973 I lived in a strange world where I work to pay for drugs and alcohol when off the rails, then October 1973 I rode down to Cornwall basically to save my life from a drug oriented existence going to about four gigs a week. I stopped all that nonsense never 👎 went to another gig gave up drugs. I stopped listening to music other than the radio. I couldn’t believe what happened when you’re on drugs – you don’t realize how it is happening to others.

Thanks to you for your article on Tim – I’m also catching up with other artists that have moved on.

With my group Reform in 1968 I was a huge fan of Tim Hardin and we used to cover How can you hang on to a dream. I’ve lately begun to featurin my music therapy work Blacksheep boy as it speaks to my own family experiences growing up.

Great write-up about Tim.

What do you make of Lenny’s Tune? How many versions are accessible? I’ve found the one on Tim Hardin 3 and there’s another one at the end of the Lenny Bruce tribute album, but this version is suddenly faded out and I wonder whether there’s a full track of it somewhere? I know the likes of Nico and (recently) Morrissey have covered it, but I’d love to hear more Tim recordings of this song.

Hi Matt, thanks for responding to our article. Lenny’s Tune is a great song, though the only version from Tim I’m familiar with is on the live album. The version from Nico is very moving as well. Thanks for mentioning the Morrissey one – I will definitely check that out.